Jenn Law, “Light Reading” from Library (2011) [https://www.jennlaw.com/barnacle-books]

Barnacle Theory

for Melville Extracted

Edinburgh University Press (2025)

“Fix your eye upon this strange, crested, comb-like incrustation,” Ishmael commands us midway through Moby-Dick. Look carefully, he continues, at “this green, barnacled thing” that sailors call the crown or “bonnet” of the Right Whale. Living on, with, and within the whale, the grotesque mass of barnacles and writhing crustaceans Ishmael describes is, in fact, its own ecological niche: traveling the whale as the whale travels, calcifying its skin and extracting plankton from ocean currents. Not much has been written about barnacles and other arthropods in Melville’s work, but this chapter argues that barnacles index, in fresh and unusual ways, Melville’s relationship to nineteenth-century scientific concepts like evolution and extinction as well as what we could call the bioarchival symmetries between the biological sciences and a more general economy of writing.

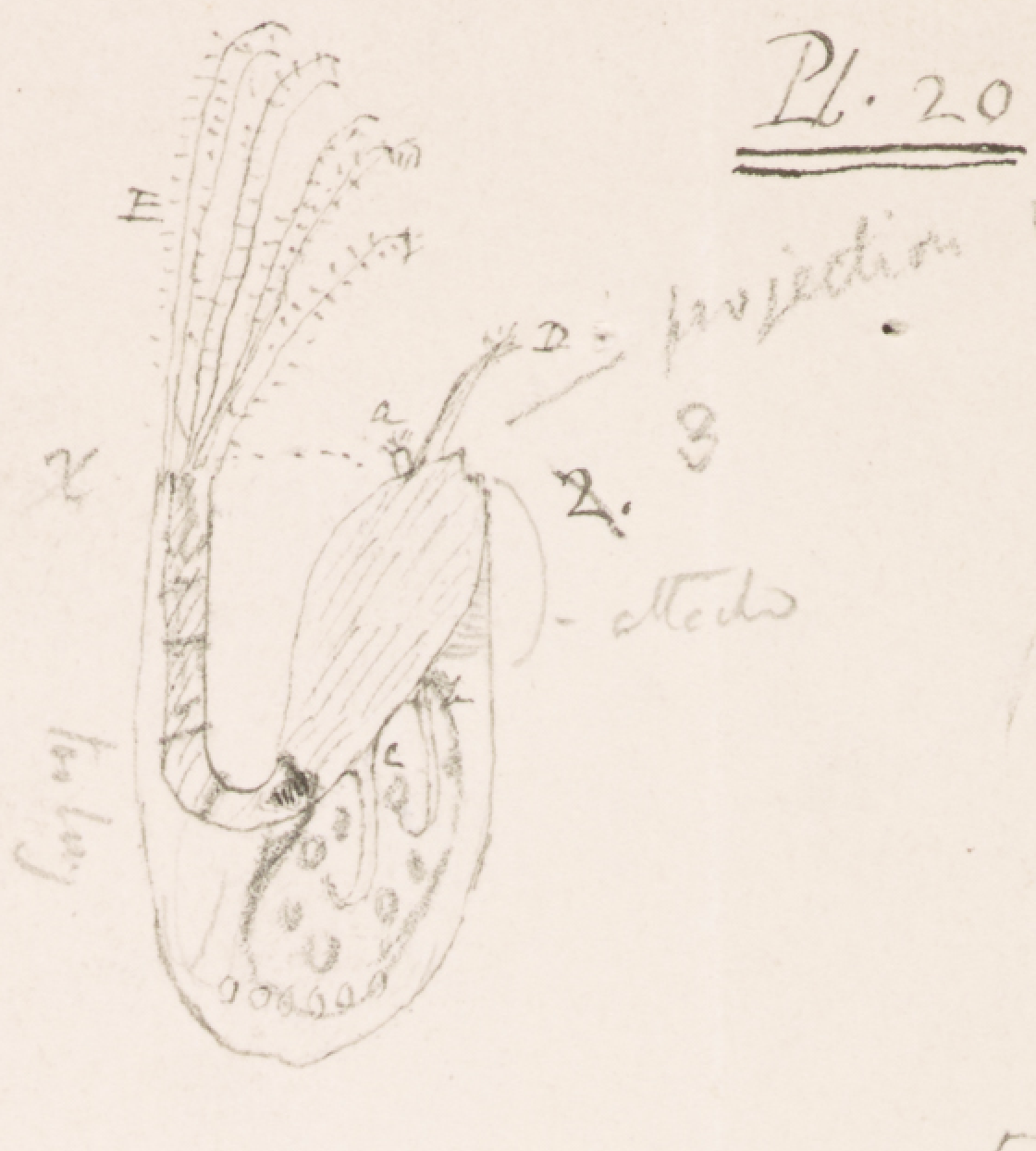

Because, rather than his studies of the famous Galapagos finch, it was actually Darwin’s work on the weird reproductive variations of barnacle species between 1846 and 1854 – culminating in his two-volume Monograph of the Cirripedia (1851, 1854) – that laid the foundation for his theory of natural selection. We now know that the extinction of barnacle species alongside their whale hosts has much to tell us about biodiversity loss and changing marine conditions (via fossilized cirripeds), but also that the evolutionary persistence of barnacles in extreme conditions provides a baseline for understanding anthropogenic disturbances on deep-sea ecosystems. Moreover, contemporary marine science suggests that barnacle biochemistry makes them extraordinarily accurate markers of whale migration routes, perceptive indicators of environmental pollution and the presence of open water nanoplastics, and even innovative future technologies (of adhesion and filtration) themselves.

Beyond Moby-Dick’s depictions of “the barnacled hulls of the leviathan” or of Ishmael cloving to Queequeg “like a barnacle,” barnacles make unexpected appearances in Mardi, White-Jacket, Benito-Cereno, marginal notes on Shakespeare, and letters characterizing Melville at the end of his life (“a weary but tenacious barnacle,” 1890). Ultimately, I theorize the presence of barnacles in Melville’s life and work, both materially and figuratively, as adaptive meshworks: biochemical and literary grafts or supplements in which structural patternings of the oceanic and the artistic collapse into a single marine grotesque. Thinking extraction through Melville’s arthropods moves us past the model of a spatialized ecosystem toward the queer, multi-temporal ecologies of holobiont extinction and highlights the architectural resistance of the barnacle-as-drag, as crusty fouler of Anthropocene pathways.